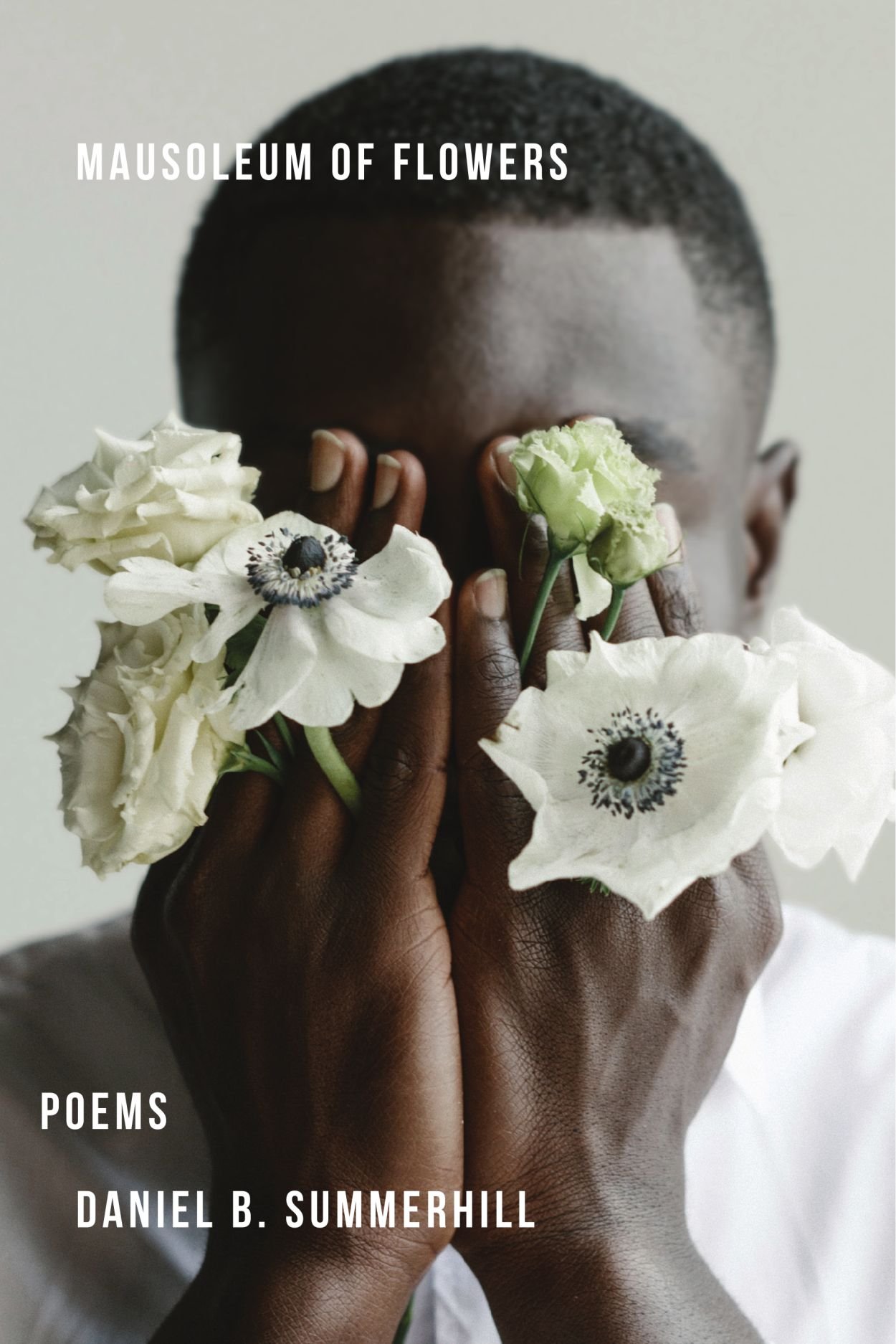

“From Kendrick to Kanye, to a Sunday in Oakland with Frank Ocean’s falsetto in the foreground, Mausoleum of Flowers is still life set against the backdrop of demise. Daniel Summerhill’s sophomore collection grabs fate by the throat and confronts it. What does it mean to continue living when your friends are dying beside you? This collection melds an exploration of spirituality and rebellion with Black tradition. Summerhill’s poems invite the reader near in order to self-excavate and explore tones of loss, love, and light.”

The assemblage of poems in Daniel Summerhill’s Mausoleum of Flowers creates an umbrella of memory through which language becomes the salve, the armor that allows these words to resurrect into something beautiful by living and reliving history. These poems are aware and cognizant of a social condition where silence is not an option, and yet, the poems are tender and loving—aesthetic beauty on the poet’s terms.

—Randall Horton, author of #289–128: Poems

A writer, who, indeed, “must have God’s attention.” What a blessing it is to see Daniel B. Summerhill render his memory in grace, in ugliness, and most importantly, in hue. These poems, though new to us, have simmered in season and in sun. What an amazing Black writer, unafraid to wrap himself in his own language. Summerhill asks questions in his work that, today, I cannot answer, so I must return.

—Jasmine Mans, author of Black Girl, Call Home

Summerhill’s name precedes him in the world of these poems where Black folks are “basking in the sun around lake merritt,” where the speakers “bleed & flowers bloom . . . american fruit.” This is a voice speaking from, not a voice speaking for. A voice declaring “i, too, am perennial.” It is the poet’s eye that redeems, making lists of what is blooming around him: an old Buick’s exhaust cloud, a collarbone forming “in a mother’s round belly,” a Frank Ocean chord progression. Nothing is left out here, not even fear, and everything that remains flowers. Reading these poems—I remember who we are, I notice redemption more. Summerhill muses on the specter of death called America, but in a place called Oakland his verse is “very much alive.”

—Joy Priest, author of Horsepower

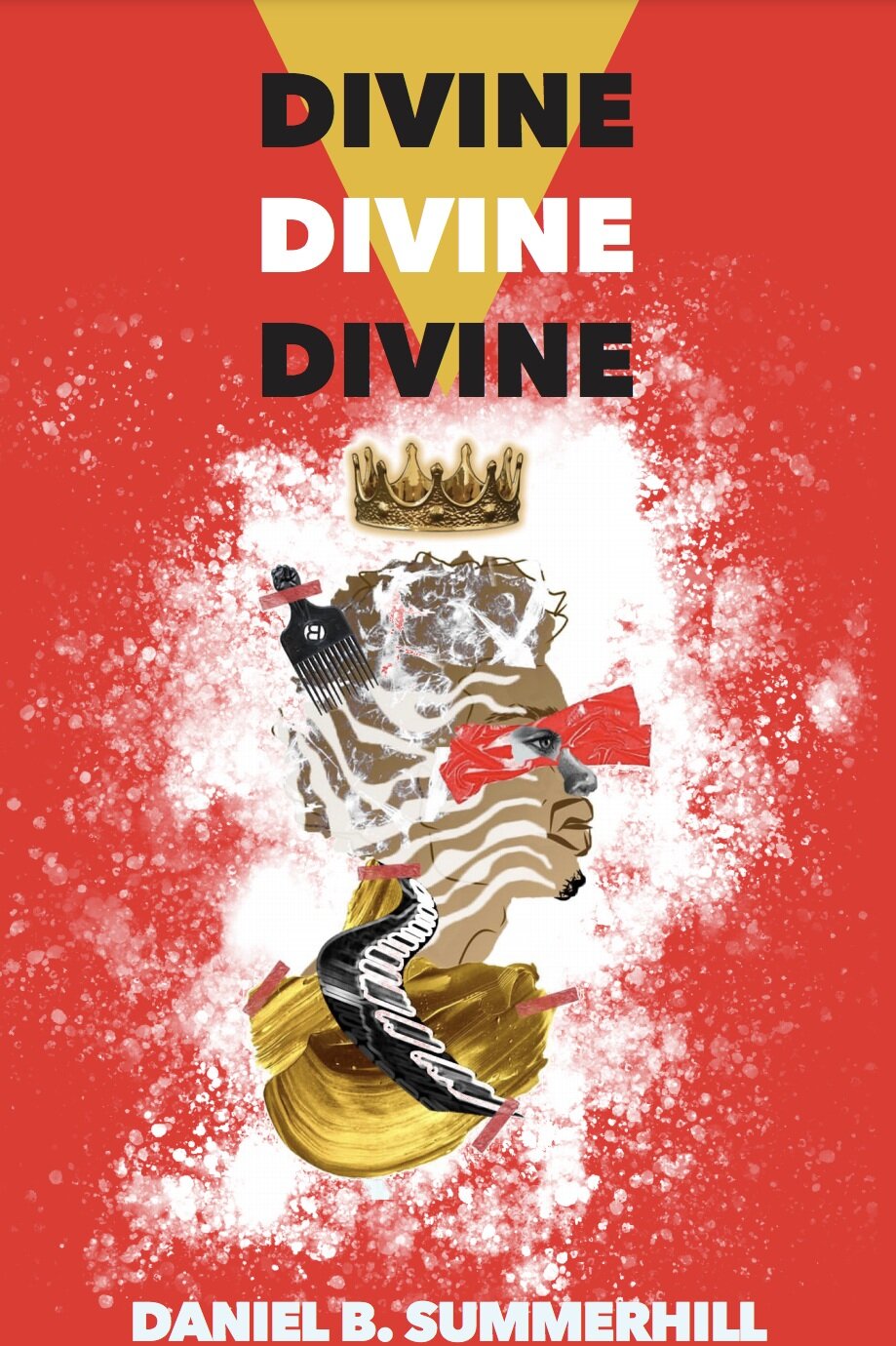

Divine, Divine, Divine is a gorgeous text with an operating principle of abundance. Summerhill sees his people capable of a great many things -- of loving, of uprooting the canon, of dancing along the sometimes treacherous lines of their own history. And for this, the poems within this book each have their own pair of wings. I was grateful to have this book as my own small mirror, through which I saw a fuller version of all my possibilities.

-Hanif Abdurraqib, Author of A Fortune for Your Disaster (2019) and They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us (2017)

Divine, Divine, Divine, is an exploration of the divine and the deviant. A consideration of the Black tongue as a home. Life and death through the lense of language. This collection is an ode to the experiences that make us whole and an acknowledgment of those things that fracture us.

The language in Divine, Divine, Divine simmers with the burn and echo of ghosts. These poems are both ode and elegy for the body and the scar it makes to mark healing and trauma. The electric doubling back to images of voice, tongue, mouth, and song ask the reader what instruments, what incantations, will keep the body safe? What must the body become when the divine is decoupled from salvation, when the best hope for a prayer is that it becomes a blade?

-Natalie Graham, Author of Begin with a Failed Body

What language do Black people have or must dig up for themselves to remember who they are, especially in a language that never intended to remember them at all? In Divine, Divine, Divine, Daniel B. Summerhill shows how Black folk make beauty out of tragic circumstances by creating that magic in poems that inhale Black life and exhale its song. Summerhill speaks to the heartbreak and music cohabitating Black consciousness, the nuances of Black identity and the permeation of racial awareness during childhood. This collection is a necessary breath in how Black language evolves, is abandoned and then reclaimed And ain’t that in itself, divine? Absolutely!

-Danielle Colin, Cave Canem Fellow, Author of Dreaming in Kreyol